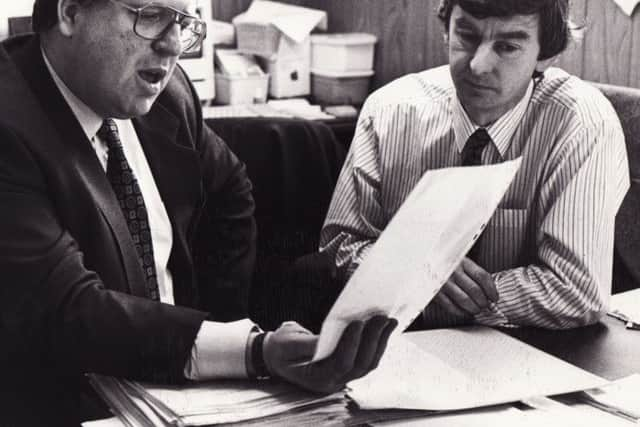

Justice campaigner Don Hale speaks 15 years after landmark Downing case

Fifteen years ago this month Mr Downing finally walked free from jail after he was acquitted for murder, overturning one of Britain’s most notorious miscarriages of justice and putting the spotlight on the Mercury’s editor.

Don Hale helped to bring the police’s case tumbling down and went on to become a celebrated justice campaigner - but his investigation eventually forced him to leave his Derbyshire home after suffering intimidation, receiving death threats and even two apparent attempts on his life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSpeaking to the Mercury from his north Wales home Mr Hale said: “I moved away for a quiet life but the case still attracts a lot of interest today and I keep getting calls from news agencies across the world.”

The Downing case would eventually change the law, win Hale an OBE and make him a go-to journalist to investigate major miscarriages of justice.

In the years since the release of Mr Downing, Mr Hale has also helped free Barry George, the man who spent eight years in jail for the murder of Jill Dando, and to clear the name of Chesterfield footballer, Ched Evans, after a controversial rape retrial.

Bakewell woman Wendy Sewell was found badly beaten but still alive in Bakewell cemetery by council gardener Mr Downing, in 1973.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was arrested and questioned without a solicitor for several hours but, aged 17 and with a reading age of 11, officers pressured him into signing a confession to the attack.

When Mrs Sewell died two days later, the charge was upgraded to murder. Mr Downing immediately retracted his confession but was found guilty at a trial at Nottingham Crown Court.

After their son had spent two decades in prison, Mr Downing’s parents approached the Mercury editor for help.

He faced obstacles at every turn, with police telling him all the evidence had been “burnt, lost and destroyed”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA turning point came when Derby Museum staff informed him that the murder weapon - a pickaxe handle - was on display there.

With Hale’s help, Mr Downing won £13,000 from the Legal Aid Board.

This paid for a modern forensic examination of the weapon, crucially revealing Mr Downing’s fingerprints were not present - although there was a bloody palm print from an unknown person.

The clothes Mr Downing had been wearing, which had been returned to his parents, were flecked with spots of blood which Hale believed were consistent with him having tried to help Wendy Sewell as she lay dying.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe news was reported in the Matlock Mercury but the articles prompted real-life drama in the form of anonymous death threats and what Hale claims was police harassment.

Letters were sent to his home and a brick was thrown through the newspaper’s window.

Most seriously, on two occasions a vehicle was driven at him at speed, which he believes were attempts to kill him.

Police even gave him a mirror on a stick to check for bombs under his car.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Hale said: “The story attracted extreme interest. I was getting phone calls from all over the world. I became a hero in Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Argentina, because I was a small town newspaper editor who had taken on the British government and won.”

Mr Downing was ineligible for parole under the law at the time because he had refused to admit his guilt.

Mr Hale took the matter to the European Court of Human Rights, winning the case in 1996. It was adopted into law that prisoners who maintained their innocence after conviction could apply for parole.

Mr Hale said then Prime Minister Tony Blair asked him for help in setting up an independent body to investigate miscarriages of justice, which became the Criminal Case Review Commission (CCRC).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStephen Downing’s was one of the first cases to be looked at by the CCRC.

It recommended his conviction should be overturned on the basis that the circumstances in which he gave his confession made it unreliable evidence that should not have gone before a jury.

The conviction was quashed in 2001 with Mr Downing finally walking free in January 2002 after spending 27 years in prison.

The legal challenge to Mr Downing’s conviction focused on the way detectives had conducted the original investigation in 1973.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had been questioned without a lawyer and there were serious doubts about whether he had been properly advised of his legal rights.

But with much more to say, Hale wrote the book, Town Without Pity, which was turned into BBC drama, In Denial of Murder, in 2004.

Police reopened their investigation, interviewing 1,600 witnesses, at an estimated cost of £500,000, but failed to identify any alternative suspect - although Hale has previously said he believes he has a “very good idea” who killed Wendy Sewell.

Mr Downing was later awarded £900,000 in compensation.

For Mr Hale however, this was the beginning of his role as a justice campaigner.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “I was invited to Hollywood and they were going to make the Downing story in to a blockbuster movie with lots of big names mentioned.”

He was soon called to help with another miscarriage of justice. Barry George was accused of killing television presenter Jill Dando but after Mr Hale’s investigation the CCRC referred Mr George’s case to the Court of Appeal and a retrial took place, when he was cleared of murder and released.

He also spent six months working on Chesterfield footballer Ched Evans’ case. Mr Evans was cleared of rape last year after an appeal.

Mr Hale, now 64, has decided not to investigate any more miscarriages of justice, focusing instead on writing books.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut after a recent appearance on television court documentary Judge Rinder in which the Downing case was revisited, Mr Hale was inundated with requests from people to take on their cases once again.

He added: “I got around three dozen emails from people wanting me to take on their miscarriage cases. It’s sad that there is little or nothing out there for people who claim they are innocent and want their cases to be looked at again. It is getting harder and harder for people to get to that stage.

“I’m proud of what I achieved.”